Goodman Games stole my idea

before I came up with it. Clearly this means that they are in possession of a time-tunnel and the HYBRID-RPG guy is on to something after all (bless his fractured soul.)

Anyway, I downloaded the Goodman Games Dungeon Crawl Classics RPG, and whaddyaknow, HIS clerics can pray for random shit too. The main difference between his system and mine is that my strictures are applied to making sure players don’t try it too often (once every ten sessions being the optimal amount of time), while making the results of the prayer pretty much up to the DM, whereas Goodman’s restrictions lie in making a granted prayer contingent on a dice roll (a “spell check”, in his system.)

That’s kind of an interesting difference, isn’t it? I suppose that it comes down to two visualizations of the same process: my rules assume that a prayer is directly beseeching the DM for his/her favor and not the “gods of chance”, so to speak, and Goodman sees it as a question of pure probability. Oh well, what can I say? I have ABSOLUTELY no problem with DM fiat, and I figure that if any character should get a little extra fiatitude it should be the cleric.

The Laws of Thrax: Clerics and Miracles

You know what’s generally just all around awesome? House rules. I love house rules, and that’s a huge part of why I love Swords & Wizardry/OD&D/LotFP/etc. Sure, you can and should house rule any system, but these games EXPECT you to do so and are simple enough that you can screw around with them without fear of making the whole game go wonky.

So, from time to time, I’ll be putting out some of the rules from my own game, for the purposes of discussion or inspiration or degredation or whatever.

Today: CLERICS AND MIRACLES.

Two sessions ago, my cleric player got into trouble and died. Well, it was pretty clear that she was going to die, but at the last second the player said “I pray for mercy!” Okay, so she did, and I decided that her goddess would shed a bit of the divine light and allow a re-roll on the Death and Dismemberment Table, and lo and behold, the cleric lived.

And that just seemed *right*, you know? I mean, clerics should just be able to pray for things, any kind of thing, and sometimes their god should hear it and perform.

A few evenings later, I came up with some rules.

At any time, a cleric can pray for something… ANYTHING. “Please heal my broken arm/cure my disease/save me from death/turn this water to wine/give the king syphilis/curse the peasants with a plague of flies/part the red sea”, anything at all.

The first question is, does the god hear the prayer? The cleric has a cumulative 10% chance per session that has passed since the last prayer attempt. So if she prayed for rain last game, the cleric has a 10% chance of being heard, but if it has been 10 sessions since the last time she has a 100% of getting through. And please note, this is since the last prayer attempt, whether successful or not.

Okay, so the god has heard the prayer. Now what? Well, the DM has to decide what happens, and that’s it. If the character is higher level, “devout” and asking for a reasonable thing in line with the god’s area of influence (“Please Diana, goddess of the hunt, send us a fat stag so that we will not starve in the wilderness”) then it should work. But if, on the other hand, the character is not particularly devout, a low level and/or asking for something that’s kind of a big deal or outside the sphere of influence of the god (“God of the Sea, please set that tower on fire”), then no, it’s just not going to happen. And if that cleric should have recently sinned in the eyes of his god or is asking for something completely unreasonable, then a full on curse or a good ol’ fashioned smiting is in order.

Which brings us to the next question: What constitutes “devotion”? And that, I’m afraid, must be left up to the individual DM and player, because I like my house rules nice and simple. But, in general, the player should be making some effort to appease his god from time to time in a manner that seems appropriate to that god’s area of influence. If he worships a god of the hunt, then prayers of thanks after a successful hunt, animal sacrifices, and feasts of wild game are perhaps in order. If he worships the god of war, then there better be some combat related rituals (meditative sword sharpening? bathing a mace in blood?) And, I would say, the more complicated a ritual and the more resources it consumes, the more pleasing it is in the eyes of the deity.

What makes a request “reasonable”? Again, that’s up to the DM, but the more mundane the request, the higher its likelihood of being granted. A 1st level cleric could probably get away with praying to heal himself, for instance, and a 15th level cleric who has given his god lots of sacrifices and performed many complicated rituals costing tens of thousands of gold pieces could call for an avenging angel to descend from the heavens and rain fire on his enemies. It’s up to the player to try and gain that worthiness, and up to the DM to decide if they have.

If any readers should wander over to this lonely little corner of the OSR blogosphere, please drop me a line and let me know your thoughts on this rule.

WTF LotFP?

I don’t QUITE know what the repercussions are, but it seems like a good sign for the scene when one of the OSR systems catches the attention of a non-gaming site like Something Awful. Congratulations on being made fun of, Mr. Raggi!

The Birth of a Macguffin

So, my game right now revolves around a classic device: my PCs are being chased because they have this thing, this important thing that a bad guy wants real bad. What’s interesting about this trope, recycled from a bazillion movies, novels, video games comic books etc etc etc? Nothing much, except that I never intended for this to happen.

So, my game right now revolves around a classic device: my PCs are being chased because they have this thing, this important thing that a bad guy wants real bad. What’s interesting about this trope, recycled from a bazillion movies, novels, video games comic books etc etc etc? Nothing much, except that I never intended for this to happen.

From the outset, this game was meant to be a stripped down Olde Schoole Adventure. My pitch was basically, “There’s this dungeon, see, and stuff inside it that your characters want, you know, riches and magic and stuff.” Not to say that the game was generic, mind you; I did my best to make the dungeon flavorful and interesting, I characterized Town as an Old West shithole run by an Al Swearengen analog, that sort of thing. But there was no “plot” to speak of.

But then the PCs started asking around about the dungeon and the history of the Thraxian civilization, and at some point I had one of the respondents tell them about this book, this Concordia Infernalis (and honestly, I don’t even know if that’s proper latin, all I know is that it sounded cool when I wrote it down) that the Thraxians were supposed to have used as a sort of WMD during their many wars, and they got really interested.

Now, here’s what I had written down about the Concordia in my dungeon key, where I had just kind of stuck it into a secret closet as one more interesting thing the PCs might discover:

8 sickly green books, 1 red leather book. Filled with horrific motifs and siturbing [sic] diagrams. If a 5th level wizard or above studies them for three months, doing nothing else, they will learn to summon 8 demons who will do their bidding. If a lawful character burns them, he/she will gain 1,000xp. If a “good” cleric burns them he/she will gain 2,000 xp AND a permanent +1 to all hit dice. Thus their god’s gratefulness is proved.

Not exactly earth shaking stuff, but when Ye Olde and Kindly Wizard told the PCs about this book, and about how it had been used by the Thraxians (I kind of played it up a bit more as they asked me questions, turning it into a weapon that could destroy armies more or less on a whim), the PCs began to treat the very idea of it with such gravity that it naturally assumed a more prominent position in the campaign. They were always mindful of checking out the books they came across in their explorations, searching for clues as to the Concordia’s whereabouts, wondering what might happen if the Ratmen got their hands on it, wondering if they could destroy it if they found it first.

And then, one day, they discovered it. And they had no idea what to do with it, finally opting to just leave it in its place, hoping that the deadly traps that had cost one of them a hand would serve as enough of a deterrent to keep their enemies from getting it. But now they were worried. When they added a powerful undead cleric (a, uh, “preserved” relic of Thrax) to that list, they got really worried.

What could I do? At this point, they needed the Concorida to be a central element of the game. Hell, with very little help from me, they had already made it a central element. So, I gave them a little push. Their employer, it turned out, had designs on the Concordia as well and betrayed them in a spectacular fashion (even if it wasn’t as fatal as it perhaps should have been), and boom, the game changed.

Now they’ve got this thing, and they’re running with it and being chased. And, despite never having envisioned this twist, I couldn’t be happier. This, to my mind, is how the game should work, it should be a synthesis of DM and player input and feedback. Not like story planning sessions or anything quite so self-consciously meta-game as that, but rather a mutual adaptability. Or, how about this? Like a ouija board with several honest participants. We are all touching the planchette and guiding it with subtle motions, but it seems to move of its own accord, to take on a life of its own and none of us really know where it is going to wind up.

The Void (and Session 25-27)

Good lord. You know what’s hard to do during a semester of grad school? Play D&D. You know what’s harder than that? Blogging about it.

Good lord. You know what’s hard to do during a semester of grad school? Play D&D. You know what’s harder than that? Blogging about it.

So, four months later and I’ve played, oh, let’s say twice. I know it was more than once, and it may have been as much as three times, but I’m going to stick with twice. Oh wait, no, it was three times. Definitely. Because I forgot about the thing and guy and killing and the death.

It’s just, Jesus. Obviously, my writing is the priority, after family, and really, D&D is way low on my list of stuff that has to get done, so really, I should be pleased that I’ve managed to do two sessions this spring.

Last time I posted, I was moaning about not having the resolve to kill off a player character that by all rights should have died. And you know what I figured out? It doesn’t matter a goddamned bit that I didn’t. Oh, maybe it undercut the dramatic climax of that particular session, but D&D is a game that goes on past those moments anyway. The next time we played, the players weren’t sneering at my pulled punch or anything, they just played. In fact, as they planned and plotted on how they were going to escape from Sylvester of the Yellow Robe’s machinations, I realized that they were pretty much as invested as a group of players could be in the scenario, so I really shouldn’t get too hung up on this stuff.

Besides, I killed that sonufabitch the next time anyway.

See, the PCs made the mistake of trying to flee certain death by running down the main road. And like any good teleporting wizard hell-bent on a scorched earth revenge, Big Bad Yellow Robe had an ambush ready to go, one that I’d worked out the week before. There was fire and screaming and a last second escape. It was awesome, and it just so happened that the guy who’d escaped death in the previous session found himself cornered yet again.

This is where it kind of gets interesting. If you’ll remember from the previous session, it was in precisely in this circumstance that my DM hand had quavered before. That time, when I should have killed him, I instead had Yellow Robe polymorph him into a frog, a circumstance that only lasted until the next dispel magic spell. This time, as Yellow Robe raised his luminescent hands, I faced the same choice.

So I had Yellow Robe polymorph the cleric into a frog again, but this time he scooped the cleric up and stuck him in his pocket. A subtle difference, but an important one.

Now here’s the best part. The froggy cleric soon found himself facing an important choice of his own. He was afforded an opportunity to escape after Yellow Robe had hunted down another member of the party (the fighter) and had him backed up against rushing River Thrax. Yellow Robe was sure to kill the fighter, and then take the dreaded Concrodia Infernalis (the current Macguffin), ensuring destruction of… well, all the normal things that get destructed, BUT the frog-cleric could use the tension filled moment to make his escape from the wizard’s unguarded pocket! And he did!

But instead of fleeing, he crept up the wizard’s robe, positioned himself just-so on his shoulder and waited. When he saw the fighter preparing to make one last, desperate stab at the nearly invincible spell caster, the frog-cleric leapt! And hit Yellow Robe square on the nose! Disctracting him! Just long enough! For the fighter’s blow to connect! Piercing through Yellow Robe’s chest!

The wizard fell to the ground, and managed with his last breath (and hit point!) to whisper his teleport spell and he was gone.

And alas, the noble frog was gone, too, disappeared to Yellow Robe’s tower, removed from the almost-dead wizard’s body and placed into a jar, with a few blades of grass and some crickets, by one of his evil servants.

Kind of neat, eh? I mean, the way that one session’s “failure of resolve” can set the stage for a pretty dramatic and satisfying episode later on down the road. True, the cleric is still not dead, but he is out of the game for the foreseeable future, and I love, love the way that his fate was based on a precedent that I had only recently lamented as a terrible mistake. Perhaps that’s a lesson: There aren’t really any mistakes in this game, just story developments that you didn’t expect.

Session 24: A failure of resolve

Last week’s session was *awesome*. This week’s session… well…

As a DM, you make plans, you consider options, try to predict where a player might go and what they might do. For me, an absolutely vital part of Olde Schoole Playe is the presentation of options. There should never be one path, one predetermined outcome, never a dead end. BUT it is important to remember that it is a perfectly valid option for players to ignore, skip over, or just not notice all of those options and find themselves in a situation that you either didn’t predict, or had hoped to avoid.

And that’s what happened this session. I scattered a few escape hatches around, along with intimations of impending doom, and yet, the characters marched blithely forward and found the inevitable awaiting them with open jaws. Here is the cliff’s notes version:

The PCs have been acting in the employ of a powerful wizard who wishes, more than anything, for them to retrieve an ancient and very dangerous artifact from deep within the Buried Castle of Thrax. Recently, they discovered incontrovertible evidence that this wizard murdered a close ally of theirs. Wishing to prevent ANOTHER villain from acquiring the item (actually, a set of 9 books), and deciding that the best course of action was to scatter the books in a number of places so that nobody could use it (sort of an opposite of your standard “assemble the mighty Rod of Kings!” quest, which I dig), the PCs got the items, and then brought them back to the surface. Where the Wizard was waiting for them. Now, as I said, they knew he was up to no good, and I had scattered both hints that he was monitoring their progress as well as potential means of avoiding the very dead end that they suddenly found themselves in, but they didn’t pick up on either. So, wizard demands the books, they refuse and begin to run away. And all Hell breaks loose.

Which was, honestly, kind of kick-ass. I mean, one fireball nearly killed all of them AND YET the PCs managed to employ a last minute, desperate distraction and delay tactic that allowed two of them to escape with their lives and several of the book volumes while the wizard murdered their comrade.

Here’s the weird thing, though. My players seemed to have a great time, even though everything went badly for them. Me? I don’t know why exactly, but I feel really conflicted about the session. Two things bother me, really– First, I’m in totally uncharted water here. I had allowed myself to believe that what happened couldn’t happen, that they’d either take one of the escape hatches I had set up for them, or make one of their own. They didn’t, and that should be totally cool, but I suddenly have no idea what the next few sessions are going to be like. But here’s the thing that really bothers me– Remember when I said that the wizard “murdered” the character who stayed behind to distract and delay? That’s what SHOULD have happened, but painfully, shamefully, I didn’t go through with it. Instead, the wizard polymorphed the character when he should have delivered a killing blow. I feel like I should just turn my Olde Schoole Cred Card in right now.

Except–

A few days later, the players are still strategizing over email about how to deal with their particular problem. In other words, nobody gives a shit about this “failure” but me. The game goes on, they’re still having fun, and the only reason I stopped having fun is because I let some preconception about how the game should have gone, and how I should have reacted to a particular situation, bog me down. That’s bullshit.

This game is about adaptability, about a story going in unexpected directions and becoming unexpectedly epic. The lesson is that I just need to let it happen.

Next time though? The mofo dies.

D&D as a folk game and the future of the OSR

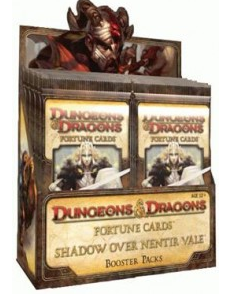

So, this exists:

These are collectible cards, sold in booster packs a la Magic: The Gathering, that offer players various bonuses during combat encounters. The idea being that a player will purchase several packs and build up a deck in the hopes of acquiring certain rare and powerful cards to enhance their characters. I note that they are explicitly optional, but I presume that they are optional in the same way that heroin might be considered optional: when everyone else is doing it, you might be more inclined to give it a try, and once you start it’s hard to stop. Hyperbolic, of course, but probably no more so than their business plan.

I guess you could say I’m not a fan.

But whatever, I don’t play that edition anyway, and the man who holds a gun to my head and makes me buy things filled his quota this month by forcing my purchase Agricola, so no skin off my teeth. But, but, BUT it does offer a bit of fuel to the fire for something I was going to post about anyway!

Here’s a definition: “Folk games are a form of structured play, have an objective, have rules, have variability, and generally need no special equipment or specific playing area. Institutional games, on the other hand, are highly organized with codified rules, played in a regulation area, and generally require special equipment.”

Interestingly, early D&D,” a game for pencil, paper and miniature figures”, meets the criteria for the former definition to a T. Later editions, and especially 4th Edition, with its battle mats and online subscription model and rigid rulesets and now booster packs, have increasingly drifted toward the “institutional” end of the spectrum to the extent that the play experience of what is ostensibly the same game as that produced in 1974 has been radically altered. This makes sense: it’s hard to make money on the shape-shifting dreams of the public domain, which is where any “folk game” will soon find itself, BUT there is an immortality there that any game designer should be happy, on some level, to have attained. D&D has always flirted with that promise, just look at the early Gygax editorials in Dragon where he fantasizes about a future where D&D has an eternal place on the shelf next to Chess, Checkers and Monopoly (a folk game with an institutional veneer), but the (perfectly understandable and by no means to be condemned) desire to make money off the IP has been an obstacle since the beginning. Witness Gygax’s push toward standardization, his hostile actions toward companies that advertised their perfectly legal compatibility, and his increasing stridency in proclaiming what counted as “Official D&D” as the 80s wore on. Of course, things would only get worse after his tenure, leading to an odd tug of war as the years wore on between a game that was special because of its ability to be “owned” by any group that cared to play it and an ever-increasing attempt to change the game so that players needed official products and support to do so.

Which brings me to a love-letter for the OSR:

The GSL/OGL/D20 thing planted the seeds, perhaps unwittingly, for a return to the “folk game” of D&D, but the Old School Renaissance were the ones who actualized the return, who more or less blew the doors down and gave the original game explicitly back to “us”, to the hobbyists, to the small gaming groups in both literal and metaphoric basements, and to any small-time designer who’d care to try tinkering with it. To the “folk” if you will. And if D&D DOES attain the immortality of poker or Mancala, or, yes, Monopoly (whose heart is still public domain) it will be in large part because of the OSR willingness to exploit the OGL.

So, when I see a post like Chgowiz’s, which expresses a real frustration with a lack of innovation in the OSR, I can’t help but think that he’s missing the point. The OSR’s purpose wasn’t to innovate, it was to liberate. No doubt, there are many talented people involved in this peculiar little scene, who have been brought together by a love of old style gaming and given a certain degree of confidence to pursue their designs by the success of the retro-clones. And they may have some really knock-your-socks-off games in them that push the RPG envelope in new and unexpected directions, and like Chgowiz, I’m excited to see what they come up with. But, I think it bears noting that when they do, their work will necessarily fall outside the scope of the so-called “OSR”, whose limits are already being pushed near to the breaking point by slightly altered spell descriptions and a changed thief-mechanic, not to mention a controversial plumbing of the Lovecraftian influences that have been a part of D&D since the beginning.

I don’t think I’m being very clear. But what I mean is this: the OSR should really be considered something that happened as opposed to a catch-all name for an ongoing design movement. By choosing to view it as the former, it becomes a starting point for new and exciting things to come, whereas the latter makes it a category, a set of limitations, “rules” if you will, about what can and can’t be included, which is anathema to creativity. So, when the innovators get to innovating, they should be willing to use the OSR as a rallying banner to promote what they’re doing, but with an understanding that the label should be abandoned the moment it acts as a limitation on their work.

Session 23: The Rats of Thrax

How can you tell if your players enjoyed the last session? Well, one possible way is to check your email a few hours later and see if you get a message like this:

We talked about it for a while and decided that we don’t want to sit around and meditate while massive rat armies horde up around us behind walls of flame. Our plan, instead, is to immediately run for it. We want to go *right now* to the western door of the office, open it, walk across the large hall to its western door (leading to the stairs), drink the potions that will disguise us as rats, open those doors, proceed to the diamond room, and boost ourselves onto the ceiling space next to poor, poor Alyssa. There, we intend to meditate a bit until Clarence can levitate our asses out of there. We’ll have our invisibility potions sort of ready to hand for in case we need to use them, and the whisk-us-to-Oz amulet ready in case all else fails. It’s an important point that we plan to drop at least one volume of the Concordia before using the Sylvester escape hatch, should we need to use it.

Putting aside the campaign-specific gobbledygook (some of which I’ll explain later) the take away here is that after the session ended and I bid them all adieu, the players conferred “for a while” about their next course of action. And concocted a multi-stage plan for the next session with well thought out contingencies. This is as good a way to tell that I got to them as I’ve ever encountered. Awesome.

So, what happened, on this the 23rd session of my 18 month long game? Well, the characters went down through three dungeon levels that they “cleared” long ago, encountered an enemy that they’ve dealt with on multiple occasions, and grabbed a magical item that they already knew was there. In other words, as far as maps, treasure and monsters are concerned, there was absolutely no new ground broken. And again, I point to the above email as proof that it was Awesome.

What worked, exactly? A lesson learned from Philotomy’s OD&D Musings.

As you may have gathered, the campaign is centered around a Megadungeon in the classic sense. The eponymous Dungeon of Thrax, as a matter of fact, which is a massive underground ruin of untold depth, ever-surprising dangers, and pervasive mystery. You know, D&D shit. For years, I turned my nose up at the very idea of such a thing for the same reason that so many forum dwellers deride it to this day: a game about kicking in doors and killing stuff, clearing level after level and hauling gold home? BORING. I want to throw the ring into Mount Doom and save Middle Earth! And, of course, what they miss and what I missed for so long is that the Megadungeon is… alive. Living, breathing, growing, changing. Not so much the walls and stones and stairs and so forth, although they certainly COULD, but rather the shit that lives down there. The monsters waiting on the other side of those kicked in doors. They’ve got reasons for being there and motives and plans and just because the players have mapped out one level fully doesn’t mean that things are going to be left alone when they head off back to town.

Exhibit A: The Rats of Thrax.

Your standard Ratman, really. Oh, they have a background, an origin story if you will, rooted in the mythic history of the dungeon, but let’s face it, they’re your average, every day ratmen. They essentially fill the same niche as goblins, a low-level, intelligent enemy that can be scaled up through numbers and cunning. To my mind, they offer a number of advantages over goblins, the most important of which is that players don’t *quite* know what to do with them the same way they do with Tolkien-esque goblinoids. Goblins you can just slaughter mercilessly and never feel too bad about it and anyone who has ever played D&D knows that deep in their bones. But ratmen? Well, maybe you can talk to them? Make an alliance? Stay on their good side? But they’re vain, and tricky, and unexpectedly clever, and a tense alliance went suddenly wrong when the players infringed on shit they didn’t know they were infringing on. A dynamic, changeable relationship, in other words, which is the heart of any good drama. Here are two entities with their own motivations forced into interaction with each other: How will it go?

And there they are, these ratmen, down in the Megadungeon, pursuing their own ends. When the players leave a room, the ratmen might very well enter, and what will they do there? It’s been wonderful for the campaign- a persistent “other” that can be kind of coexisted with, or at least avoided, but that is always *up to something*. And the ratmen have gotten to my players moreso than any other monster, trap or circumstance, to the point that last session, I SWEAR to you that the players, sitting in their living room playing a skype D&D game, suddenly realized that they’d been whispering to each other for fear that the ratmen in the dungeon might hear their out-of-game conversation.

I steeple my fingers and intone in my best Montgomery Burns voice: “Excellent.”

(PS: That totally awesome ratman pic was drawn by Erik Loiselle, and can be seen in its original form HERE. You can buy a print of it, or a greeting card. For ratman themed holidays.)

Briefing for a descent into Thrax

Tomorrow, my group and I will have our 23rd, no 22nd, no 17th, no 25th session. By which I mean, we will have the next session in our line of sessions stretching back to May ’09, and I really wish I had kept a little better track of these things because, although it surely doesn’t matter to anyone, least of all me (in any real sense), I wish I could point to a real, definite number and say “See! 23 sessions! So!” But I can’t. Instead, I will do what any good DM does and choose something kind of arbitrarily and then commit.

Tomorrow, my group and I will have our 22nd session. Yes, 22 sessions of dungeon delving the Old Schoole Way, 22 sessions of blood, routs and slaughter, 22 sessions of houserules tried and backpedaled on, 22 sessions of “Oh, please let them open this door… please, please, please.” And today I am preparing.

Here is what “preparing” means to me: Staring into space, picturing how it might go; Practicing NPC voices (because when you have a primary antagonist with a Count Floyd accent, you can’t not practice it every chance you get); and, of course, toying with the idea of actually stat-ing up The Villain, but somehow finding better things to do. The single most wonderful thing about the Old School Way is that I’m pretty sure I could stop all preparation right now and still have a perfectly enjoyable game where my players don’t suspect that I’m shirked DM-duties. But today is a “preparing is half the fun” kind of day, so I’m going to go ahead and whip up that Villain and jot down a few notes about things that have changed in the dungeon since their last adventure. Today, I’ll enjoy it, but I’m happy to have the option about how much energy to expend on it.

What I play, and why I play it

Three years ago, I lived in Austin and I GMed an Ars Magica campaign. And it was awesome. But god was it hard. Labor intensive. I’m talking historical research, philosophical rules debates, wiki page management, hour long character generation, hour long spell creation, primary player characters, secondary player characters, tertiary player characters, troupe-style GMing, point-allocation home-base creation, spread sheet inventory management, and formulae for figuring out how long it takes to read a frigging book. Like I said, I LOVED it, but I would spend hours each week working on aspects of the campaign and STILL have anxiety attacks before games. When I moved away and the campaign necessarily came to a close, I was sad that the story was over, but not exactly unhappy about losing that particular source of sleepless nights. In fact, I thought that maybe, just maybe, I might be done with RPGs altogether.

But then, about two years ago, the itch came back. If you’ve played or GMed RPGs, you probably know what I’m talking about. An idea bubbles up to the surface of the brain, a vision of a war-torn kingdom or a doomed spaceship or a walled village on the edge of an irradiated jungle. Something that plucks at the synapses for a while and inspires a run of daydreams, but nothing that I’d really like to write about. And the choice for me has always been to either forget about it, simply let it slip back into the subconscious and fade away, or, in the words of Principal Skinner, make a game of it.

So there I was, newly returned to the city of my birth, Albuquerque, NM, with that old RPG itch asserting itself, when a friend of mine invited me to his D&D game.

Truth be told, I had been done with D&D for about a decade and didn’t really relish the idea of returning. But I had really enjoyed it once upon a time, and the more I thought about the things I had liked, the more interested I was in reacquainting myself with it. Besides, it was a new edition, the 4th, and I was curious to see what had become of my lost love in the hands of Hasbro & co. So, I said yes, and I played a few games.

Long story short: I hated it. Too rigid, too different than what I remembered, too many frigging numbers to enter on the character sheet, too many hours spent on the same damn fight, too little time to spend trying out crazy ideas and causing miscellaneous trouble. BUT, the old D&D embers were still smoldering somewhere inside me, and just enough fuel had been added that I now actively wanted to find the game that I remembered. So I did what every other unfulfilled role player does: I took to The Forums. At the time, they were filled with 4e backlash and counter-backlash and counter-counter backlash and you get the idea, and I got a certain thrill reading over the various bile filled invectives for and against, and somewhere buried in the muck and slander I found a link to Grognardia, and thence to Swords and Wizardry.

When my old RPG group reasserted itself through the magic of Skype, Swords & Wizardry: Whitebox became our game of choice. Here’s what I like about it:

– No brainer setting. There’s nothing to explain, we all know what D&D is like. Wizards and warriors and elves and dwarves and all that shit. Nothing to explain. Now, as we’ve played, the setting has grown in its own quirky direction, and there are hints of a cohesive world that assert themselves in our sessions, but aside from a one paragraph setting pitch I sent my players at the beginning of the campaign, I’ve NEVER had to explain anything outside of play.

– Stripped down, classic D&D mechanics. Look, D&D has always kind of been an ugly system that doesn’t make a huge amount of sense if you think too hard about it, but in its original form it offers the Prime RPG Virtue of Staying Out of the Way. Rules look-ups are nonexistent, monsters and bad guys take about 4 minutes to fully flesh out (or 30 seconds to whip up on the fly), characters can be generated in 10, every one knows how a fight goes down and everything else can be improvised. Which brings me to

– House rules are welcome– Now, I know that any decent group will probably house rule every single system that comes their way, but the law of unforeseen consequences can play hell with some of the more complicated rulesets out there. There’s something comforting about tinkering with a minimalist system in that it’s easy enough to leave the parts of it that work alone and focus on the stuff that you want to change in isolation.

– The tropes– And by this, I mean the rules, not the setting. Clerics turn undead, magic users are pasty weak fellows who later blossom into destruction engines, fighting men are the utility class, and every once in a while a poison needle pricks you and you save or die. Yeah, these things are weird and quirky, but they’re also uniquely comforting. D&D is the comfort food RPG, and god love it for being so.

Now, you’ll notice that I’m pretty much using Swords & Wizardry and D&D interchangeably, and that’s on purpose. S&W isn’t really a game in its own right, it’s a (and please understand that it’s still kind of hard for me to use this term with a straight face) “retroclone”, which is to say, an imitator of the original Dungeons & Dragons edition from the late 70s with a few modifications, so why pretend otherwise?

So now, something like 18 months later, I’m running a more-or-less biweekly game with my old players, and we’re loving it. It’s a blast, and it doesn’t require any more sleepless nights to keep it going. Oh, way back at the beginning I did a bunch of work designing dungeon levels and so forth, but these days I only need an hour or so of prep time before a session and I love that. At this point anyway, I don’t see myself wanting to play anything else.